AI, Corporations & the Morality of Artificial Agential Systems

Abstract

The parallels between the moral problems raised by AI and corporations are commonly referenced, but the depth of their overlap is more than incidental. I argue that corporations and AI can both be categorized as artificial agential systems (AAS), a group of entities which pose unique moral problems relating to responsibility, accountability and agency cultivation. Considering AAS as a whole allows us to jointly address longstanding debates in each domain and reveals tangible opportunities for improving our moral environment. The paper illustrates the parallels in problems of moral responsibility between corporations and AI, particularly regarding agency and the compontentized makeup of the systems. I argue that both systems are sociotechnical in nature, and that the technical elements of each system actively minimize human agency. I consider whether this can be reduced to the problem of many hands, but rebut the argument through further illustrated this tendency to minimization and human agency disintegration. I propose that a revised moral framework—one that recognizes the distinct agency of AAS and emphasizes the cultivation of human moral agency—offers a more effective path for integrating these systems into our moral ecology and addressing the novel ethical risks they pose.

1. Introduction

In December 2024 the CEO of a major U.S. health insurance company was shot and killed, allegedly by a man with grievances over the company’s handling of healthcare coverage 1. The U.S. public was split on the morality of the act, with many surprised by the significant support the accused garnered (Meko, 2025).

Meanwhile Elon Musk, currently the world’s richest person, vigorously debates whether highlighting the dangers of autonomous vehicles is morally acceptable, saying, “If, in writing some article that’s negative, you effectively dissuade people from using an autonomous vehicle, you’re killing people” (Bohn, 2016).

Despite a great deal of discussion, there is little consensus on how the actions of corporations and artificial intelligence (AI) fit into our moral landscape. AI is relatively new as a technology, and our moral practices are catching up to technological progress. And while corporations are not novel, their increasingly dominant societal presence has made the blindspots in our moral ascriptions more apparent.

In both cases, we notably run into the problem of moral responsibility gaps. Moral responsibility describes a set of practices including our ascriptions of who or what is accountable, attributable or answerable for an event or outcome. This differentiates moral responsibility from other concepts of responsibility like legal responsibility (wherein we consider legal liability) or causal responsibility (who or what led to an event occurring)2.

Moral responsibility gaps exist where we have a morally loaded outcome without an adequate target for accountability or responsibility. The outcome must be morally loaded, meaning that it is morally good or bad (Floridi, 2016), to discern from acts of nature, luck, and other outcomes that may be tragic or favorable but without moral valence.

I show that corporate and AI ethics face many of the same ethical questions and argue that this is because they are similar types of systems, which I call artificial agential systems (AAS). This categorization implies that not only are the ethical questions the same, the answers are the same. I argue that this categorization untangles long-running debates in both the corporate and AI cases, and illuminates productive pathways for future analysis.

To do this, I describe the major turns and questions debated in the cases of both corporate moral responsibility and AI and moral responsibility. I then outline relevant parallels between the debates and show that the parallels exist because AI and corporations are the same type of system. With an understanding of the overarching system behavior, I show how analysis at the category level can advance both debates.

I further describe the behavior of AAS by addressing two objections: that my categorization is not apt (corporations and AI are distinct in relevant ways) and that it does not abstract at the appropriate level (we can categorize the problem more broadly).

2. Moral Responsibility & Corporations

Corporations play a dominant role in society and regularly exact morally loaded consequences on the people and communities with which they interact. Many people are employed as attorneys of corporate law, auditors and regulators, responsible for litigating and mitigating issues of causal and legal responsibility. Perhaps these well-formed systems of responsibility ascription lead us to reflexively look for the same when it comes to corporate moral responsibility — who or what can be held accountable when corporate actions have morally loaded repercussions.

In the literature on moral responsibility and corporate activity, the debate is generally framed against proving whether or not corporations are appropriate vessels for moral responsibility, as they are for causal and legal responsibility.

Pettit, individually and with List (List & Pettit, 2013; Pettit, 2017), has influentially argued that corporations are a type of group agent. Group agents must meet specific requirements for agency, and corporations in particular meet both those and additional specific requirements for being moral agents.

To be a moral agent, an entity must a) be an agent and b) must be able to be held responsible for its actions. Holding responsible is different from thinking an entity is responsible. In the latter case, the entity is merely a candidate for praise or blame. Holding responsible is the activity of blaming or praising an entity. If an agent is fit to be held responsible, it meets the criteria for being a moral agent.

List and Pettit offer three criteria for an agent to be able to be held responsible for a particular choice:

Normative significance: The agent must have been faced with a morally significant choice. It must have the opportunity to choose between a right and wrong action.

Judgmental capacity: The agent has the appropriate information needed to make a considered decision, and the capacities and understanding to choose between available options.

Relevant control: The agent is able to make the choice (i.e. it has control over its decision).

List and Pettit 3 hold that each of these criteria are necessary for fitness to be held responsible, as an agent who does not face morally significant choices, does not have the appropriate information or capacity to judge a decision, or is unable to autonomously make a choice is unlikely to be held to be morally responsible for an action. They also hold these are sufficient criteria, as someone who meets these criteria would be hard pressed to argue that they should not be fit to be held responsible.

Critics argue that corporations do not meet these criteria (Moen, 2023; Rönnegard & Velasquez, 2017), that these are the incorrect criteria from which to judge (Sepinwall, 2017), and that attributing moral responsibility to corporations is at best useless, and at worst harmful (Hasnas, 2017).

2.1 Corporations Do Not Meet Pettit’s Criteria

Rönnegard and Velasquez (2017) outline six arguments against attributing moral responsibility to corporations, two of which target criteria for holding corporations responsible. Similarly, Moen (2023) argues that corporations do not meet the control condition.

Rönnegard and Velasquez argue that corporations do not have mental states, therefore cannot meet the second and third criteria. They cannot meet the criterion for judgmental capacity because corporations do not hold their own beliefs and desires. While we often attribute beliefs and desires to corporations, this is merely metaphorical. That is, it is inaccurate to reference beliefs or desires to describe or explain the actions of a corporation. These actions can be better described by referencing processes, actions by members, and the architecture of the corporation itself, among other things.

Without mental states, a corporation cannot be said to understand why it has chosen between available options. The corporation does not have considered reasons for its actions.

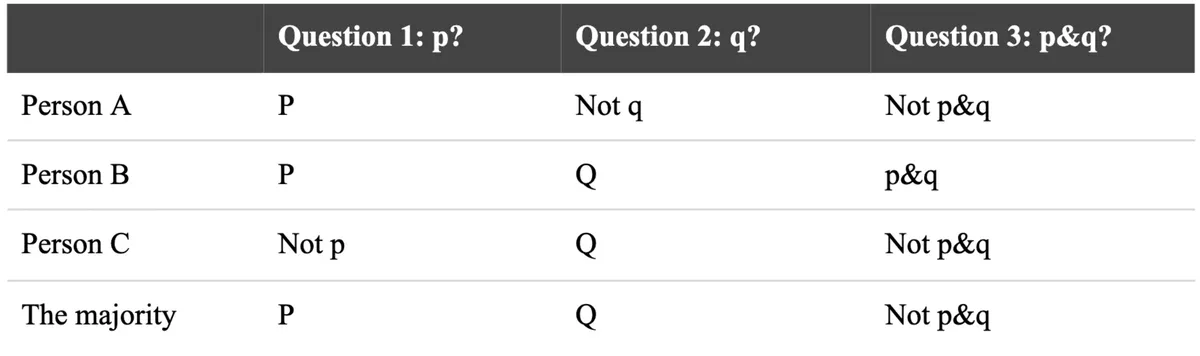

Pettit considers metaphorical attribution, however, and describes a discursive dilemma which could occur in a corporate setting. The discursive dilemma shows how some decisions a company makes are irreducible to the beliefs and preferences of the membership. In fact, in Pettit’s example (2017) the corporation takes a decision opposite what any representative member would prefer (see Table 1).

Table 1

An illustration of a discursive dilemma (Pettit, 2017).

While this is meant to underline the control condition corporations must meet to be held responsible, Moen (2023) argues that this is not enough, as the membership’s capacity for strategic behavior (they could figure out the game and vote accordingly) keeps the ultimate control of the situation with them.

While this is meant to underline the control condition corporations must meet to be held responsible, Moen (2023) argues that this is not enough, as the membership’s capacity for strategic behavior (they could figure out the game and vote accordingly) keeps the ultimate control of the situation with them.

2.2 Methodological Issues

Perhaps the issue with holding corporations morally accountable precedes Pettit’s criteria. Rönnegard and Velasquez (2017), and more expansively Sepinwall (2017), argue that the method Pettit uses for assessing fitness to be held responsible misunderstands the practical application and goals of our moral practices.

The argument builds off of Strawson’s foundational work (2008) on reactive attitudes where he identifies second-order attitudes people have when they are the actor or subject of moral judgement. These attitudes and reactions like resentment, gratitude and forgiveness are inextricable elements of our moral practices.

As Sepinwall emphasizes, reaction to moral praise or indignation is more than cognitive: it has an important emotional element which lends these practices their efficacy. The emotional impact of being the target of blame, for instance, is part of its punitive force. Rönnegard and Velasquez also stress the importance of emotion in our moral practices, adding that without emotion one is unable to fully and accurately understand moral standards.

Without emotion, corporations could meet Pettit’s criteria to be held responsible and still be inadequate targets of moral responsibility. The argument is not that without emotion praise and blame do not serve an adequate regulatory function on future action. It is that without emotion the practice of holding morally responsible is misdirected. It’s like cutting a sandwich with a spoon. You may end up with two pieces of sandwich, but it is not the appropriate use of the tool (and there are better cutlery options to get the outcome you’re looking for).

2.3 Corporate Moral Responsibility is Unnecessary

Even if corporations could be held morally responsible they shouldn’t be, Hasnas (2017) argues. Denying corporate moral responsibility doesn’t mean we can’t assign any type of responsibility. We have significant structures to accuse, judge and redress situations of civil liability, administrative responsibility, and metaphorical responsibility (the figurative ascriptions people commonly attribute to companies).

Moreover, ascribing moral responsibility to corporations opens the door for injustice. Moral responsibility implies that corporations can be subject to criminal punishment, but criminal punishment cannot target a corporation because the corporate entity is not an individual subject. Any punishment of the corporation necessarily is punishment for persons downstream: corporate members, employees or consumers of the corporation’s products and services. This is unfairly punitive to innocent people (consumers, for instance, have no role in perpetrating corporate malfeasance). “Corporate punishment is inherently vicarious collective punishment,” (Hasnas, 2017, p. 100). Rönnegard and Velasquez (2017) offer a similar critique.

Floridi (2016) attempts to bridge this by altering the concept of moral responsibility in distributed settings like corporations. Rather than holding corporations morally responsible like we would hold an individual morally responsible, we can develop a concept of faultless responsibility. When a distributed system does a morally loaded action, faultless responsibility would be distributed equally to all causally-relevant nodes in the system regardless of intention. In a corporation, responsibility might be distributed to causally-relevant employees and members, for instance.

Floridi sidesteps the question of collective punishment by stressing that the distributed moral responsibility must be faultless in nature, a strict liability where "there is no requirement to prove fault, negligence or intention" (2016, p. 8). Responsibility could be distributed using a method of backward propagation, similar to how neural networks are trained to generate more favorable outputs.

With a system of faultless responsibility, corporate moral responsibility also becomes unnecessary. Responsibility is distributed from the corporation to the nodes of the system which receive appropriate faultless praise or blame.

Even so, if corporations are not fit to be held morally responsible, we face staggering gaps in our responsibility ascriptions. Pettit points to an “avoidable shortfall in the regulatory effects that our responsibility practices are generally designed to achieve. We will leave a loophole for people to incorporate for socially harmful but selfishly rewarding ends, and to do so with relative impunity” (2017, p. 33).

I address this moral responsibility gap more below.

3. Moral Responsibility & AI

Debate concerning the moral responsibility of artificial intelligence (AI) tends to focus less on whether AIs are fit to be held morally responsible, and more on where moral responsibility falls given that:

- An AI’s actions can be morally loaded, and

- An AI as technology is not an appropriate target for moral responsibility

Matthias was early to describe this responsibility gap problem (2004). The design of AI systems involves creating a hidden decision layer between the system’s input and output. In the decision layer, inputs are driven through an intricate series of weighting algorithms which branch through potential solution paths, converging on an output which is ostensibly based on the node weighting tuned through previous training. This decision layer is “hidden” in that it is a black box for humans. The criteria for weighting across the millions or billions of nodes is not symbolic — it does not correspond to human concepts — and the network’s massive complexity makes it impractical to untangle and analyze.

In cases where an AI makes a morally loaded and unpredictable action — imagine a surgical robot going forward with a risky medical intervention which ends up failing, or a recruiting software which systematically rejects applications from women — we are left with a responsibility gap. The standard view is that this gap comes from a lack of two general conditions of responsibility: the epistemic condition and the control condition (Coeckelbergh, 2020). The epistemic condition dictates that to be morally responsible one must know what they are doing. The control condition requires that one must have sufficient control over the action in question. Note that these criteria are similar (though not equal to) Pettit’s criteria for group moral agency.

If the AI’s action was neither predictable nor controllable by the system’s developers or users, neither can meet these responsibility criteria. Likewise, the AI does not seem to have “knowledge” of its actions and does not have the appropriate kind of control over its outputs to be morally responsible.

The responsibility gap is posed as a problem for our normative understanding of moral responsibility. As people continue to create, operate and rely on AI systems for important societal functions, how do we ascribe blame (or praise) when something goes wrong (or right)?

3.1 Use the Tools & Targets We Have

Multiple philosophers have offered solutions to bridging or dissolving the AI responsibility gap, citing pre-existing responsibility practices and targets.

Nyholm (2018) and Himmelreich (2019) suggest we look to the users of the systems for ascribing responsibility. Our relationships with AI is not such that these systems are off acting entirely without human action. There are people using the systems. Nyholm argues that this creates a situation where collaborative responsibility can be appropriate. Users maintain a relationship of moral responsibility by virtue of being the only party involved which is a fully responsible moral agent. In the case of autonomous weapons systems, Himmelreich similarly argues that a military commander could be seen as reasonably responsible for the actions of the autonomous system.

Or perhaps through deliberate system design we can both improve the possibility of users to assume responsibility or be responsible, and affect the allocation of responsibility among the users and other affected groups (Nihlén Fahlquist et al., 2015).

Nihlén Fahlquist et al. differentiate between backward-looking responsibility and forward-looking responsibility. Backward-looking responsibility is the responsibility I’ve addressed so far. It is assessing responsibility based on certain criteria an agent either meets or does not. Forward-looking responsibility is responsibility seen as a virtue. Forward-looking moral responsibility practices are a continuous habituation and development of responsible dispositions, attitudes and actions rather than specific requirements.

Technologies, and AI systems, can be designed to promote both, and Nihlén Fahlquist et al. offer twelve design heuristics to help accomplish this. Relevant to this discussion, they recommend designers distribute responsibilities created by the system fairly, effectively and completely (i.e., such that “for each relevant issue at least one individual is responsible,” (2015, p. 486)). Following these guidelines we necessarily close the moral responsibility gap.

Where morally loaded actions aren’t genuinely blameless, Hindriks and Veluwenkamp also invoke system design (2023), proposing the existence of a control gap rather than a responsibility gap. A control gap is risk-based rather than capacity-based. When a system has an unacceptable level of risk of behaving unpredictably it can be said to display a control gap. These control gaps can be “decreased, if not avoided all together” by improving the system’s ability to “emulate guidance control” and through safety engineering (proactive and reactive safety barriers) (Hindriks & Veluwenkamp, 2023, p. 21). Thus we close the responsibility gaps by placing relevant subsystems “under meaningful human control” (ibid).

These solutions sidestep the issue, however. Responsibility gaps can exist in situations where an AI user is acting ethically appropriately. The users that Nyholm and Himmelreich target have knowledge of the morally loaded potential of their systems’ actions, but we can’t always rely on this. Likewise, Nihlén Fahlquist et al. and Hindriks and Veluwenkamp offer meaningful ways to avoid responsibility gaps, but unsatisfying results in addressing problems of the gaps as they exist in the world.

Rather than targeting the closest individuals, Tigard (2020) recommends we use our pre-existing moral practices in cases of morally loaded AI outcomes. Blaming, praising, or expressing our reactive attitudes toward AI that create these outcomes is normatively appropriate, Tigard argues. Though the system may be insufficiently responsive to such attitudes, we can then move to an objective stance and use other accountability practices like sanctions and behavior correction to improve the AI’s future actions.

Focusing on pre-existing practices ultimately leaves us as unsatisfied as changing our targets. We already use our pre-existing moral practices, and the gaps still seem to exist, particularly concerning backward-looking responsibility. Tigard stresses that our moral practices are much broader than accountability, but does not offer satisfying responses to how to address accountability for deeds done.

3.2 Develop New Responsibility Practices

If we can’t use the tools we have, perhaps we can broaden our moral practices to acknowledge our increasingly networked and complex world.

Responsibility attribution above is largely focused on individual responsibility: which individual persons or systems can hold our responsibility ascriptions?

Taylor (2024) discusses efforts to extend our responsibility ascriptions in cases of AI action to a collective rather than a single or set of individuals. Those people involved in the development, design and deployment of AI systems may together be considered a collective entity with its own, separate agency (similar to Pettit’s corporation). Should these groups also exhibit moral agency, they become adequate targets for responsibility ascriptions. Taylor concludes, however, that this collective responsibility will not be adequate to address the moral costs responsibility gaps can create, and the gaps’ effects remain.

Goetze (2022) offers a solution in which we alter our responsibility practices to accept blameless responsibility on the part of AI systems’ developers and designers for morally loaded AI actions. Goetze’s vicarious responsibility is similar to Floridi’s faultless responsibility in that both have connected individuals accepting responsibility for an outcome without having personal agency in said outcome. Goetze does not suggest splitting the blame equally among nodes as Floridi does. Instead, a system’s developers can take responsibility for an AI’s morally loaded actions without the moral demerit (or merit) that goes with being held responsible.

Stahl (2006) turns not to the developers of the system but to AI and autonomous systems themselves, offering that we can alter our moral practices to ascribe quasi-responsibility to these systems. He takes an instrumentalist view of responsibility, stressing its nature “as a social construct of ascription, aimed at achieving certain social goals” (2006, p. 206). With this in mind, we can attribute a responsibility without reference to agency or personhood — the quasi-responsibility — to the systems themselves. The responsibility would be with “the purpose of ascribing a subject to an object with the aim of attributing sanctions (the heart of responsibility) without regard to the question of whether the subject fulfills the traditional conditions of responsibility” (2006, p. 210).

While Goetze and Stahl’s arguments are grounded in pre-existing, everyday moral practices, they flatten the notion of moral responsibility and ignore much of its depth in our lived experience.

3.3 Reconsider Our Method

How then can we appropriately address responsibility for the morally loaded outcomes of AI systems while fully acknowledging the roles and nature of morality? If we fully acknowledge the nature of morality individually and societally, perhaps we’ll find that we have misconstrued the problem.

More so than assigning praise and blame, moral responsibility is a relational and practice-based phenomenon. It is focused on actively cultivating and maintaining moral agents; praise and blame being only one feature of the system. Vallor and Vierkant (2024) draw out this distinction, pulling from Strawson (2008) and Vargas (2013, 2021). They argue that responsibility gap debates are best directed not only at how best to ascribe praise or blame but also how to best create a healthy moral ecology.

This is a much more forward-looking account of AI responsibility. Vallor and Vierkant argue that the moral performance of an AI system is derivative of the moral maturity of the developers, users and regulators of the system. Therefore, in cases where our typical backward-looking responsibility attributions fail — in cases of responsibility gaps — “an open-ended suite of other responsibility practices remains available to us, including answerability and accountability practices understood proleptically” (Vallor & Vierkant, 2024, p. 12).

In order to fold AI into our moral ecology, Vallor and Vierkant allow for both using tools we already have and developing new responsibility practices. But by focusing on cultivating moral agency in people, a new way to untangle the responsibility gap problem appears.

Much of our moral practice has developed in order to change the future actions of ourselves, other people and groups of people. The reactive attitudes, a constitutive element of our responsibility practice, are meant to invoke moral emotions in their targets as much as they do in their subjects.

But as Tigard (2020) points out in the case of AI, and Sepinwall (2017) does in the case of corporations, our reactive attitudes can be met with silence. Our moral practices break down in cases where we are in a moral relationship with a system, which creates morally loaded outcomes but is not an appropriate target for moral responsibility itself.

This lack of mutual recognition is a gap far deeper than a responsibility gap. Vallor and Vierkant deem this a vulnerability gap. AI does not have the appropriate emotional, social and cognitive capacities to be vulnerable in the same way humans are. This vulnerability asymmetry leads not only to apparent responsibility gaps but also potential agency disintegration, wherein a human delegates responsibility for a choice or action to a system which cannot hold the requisite moral obligations concerning its execution.

Reframing the AI responsibility problem as a problem of mutual recognition and identifying the goal as improving our moral ecology opens up new avenues for innovation, but does not resolve the how of integrating AI into our moral ecology.

4. Addressing Artificial Agential Systems

As you can see, corporate and AI morality discussions traverse similar terrain. Could typical moral practices account for the actions of these systems? Do criteria for human moral agency transfer to them? Can responsibility for these systems’ actions be distributed to associated people? And beneath it all there lies a debate-altering distinction between criteria-based accounts of moral agency and holistic or virtue-based accounts. What we additionally will find is that not only are the questions the same, the answers are too.

Vallor and Vierkant (2024) note the similarity between corporations and AI in their work surrounding the AI responsibility gap. Sepinwall (2024) and List (2021) analyze the similarities from the corporate/group agency starting point. The overlap of these discussions is not coincidental — corporations and AI are similar entities in many respects. Sepinwall (following Reyes, 2021) groups them as artificial systems, meaning they are human-originated (i.e., artificial) goal-directed groups of components working in a coordinated manner to achieve those goal(s) (systems). List identifies the key parallel between group agency and artificial intelligence as “the fact that both phenomena involve entities distinct from individual human beings that qualify as goal-directed, ‘intentional’ agents, with the ability to make a significant difference to the social world” (2021, p. 1218).

I am limiting my discussion to corporations, not all group agents, for reasons I’ll make clear shortly. To move forward, I take List’s insight into the agency of these systems and add it to Reyes and Sepinwall’s emphasis on human origination.

Corporations and AI share significant parallels because they are both artificial agential systems (AAS). Agency for this definition includes basic requirements of agency, what Nyholm calls “domain-specific basic agency: pursuing goals on the basis of representations, within certain limited domains,” (2018, p. 1207). Of course, systems with higher degrees of agency also qualify as artificial agential systems, but the agency threshold is low.

This basic agency requirement separates the relevant systems from artificial systems which would not have the same problems when it comes to ascribing responsibility, like a mechanical loom or a sufficiently small business.

Having identified AAS, we can now better identify the problems of moral responsibility ascription discussed above. Rather than separate questions; “how can we ascribe moral responsibility to the acts of corporations” and “how can we ascribe moral responsibility to the acts of AI systems” we can ask “how can we ascribe moral responsibility to the acts of artificial agential systems?” The answer should apply to both corporations and AI.

Indeed, through our tour of the debate on AI and corporations above, we can identify ways in which combining the discussions will move both forward. A large part of the discussion on AI, for instance, bypasses whether AI systems are fit to be held responsible (apart from future-oriented discussions). As we’ve seen, corporations’ fitness to be held responsible is in dire straits. Participants in both discussions have also attempted to distribute responsibility to humans involved in the systems. In both cases they have failed, and for the same reasons: they ignore crucial aspects of our comprehensive responsibility practices. Thirdly, there are compelling arguments in both domains that moral responsibility is not just an atomist question of meeting certain conditions. Moral responsibility is part of a continuous cultivation of moral agency. The effort to untangle multiplying knots concerning responsibility ascription will be less effective than a coordinated practice which humanely folds all agential systems we create into our moral ecology.

There are immediate practical benefits as well. Society’s broader approach to responsibility in the corporate arena is well formed, and there is robust infrastructure in place, particularly on questions of legal and causal responsibility. AI responsibility frameworks can build off of this. AI, for its part, benefits from a currently dizzying pace of experimentation and technical progress. Moral innovation in the AI domain can be applied to similar questions for corporations. We can more effectively incorporate these systems into a working moral ecology by addressing them and other artificial agential systems as a group.

Perhaps there are good reasons not to combine the discussions. Pettit and List describe corporations as group agents, and are thus dependent on human constituency. AI are not group agents (which can include entities like clubs and political parties) and thus it would be more fitting to designate AI, which is autonomous from human intervention, separately.

On the other hand, perhaps our dissolution of the problems does not go far enough. Rather than grouping the problems present as problems of AAS, we can better characterize the moral responsibility issues around corporate and AI action as the familiar “many hands problem.” After all, if AAS do not present as moral agents, responsibility and our ascription practices must cascade to those who do 4.

I argue against these positions in the next two sections.

5. AIs & Corporations are Too Different

List and Pettit introduce a commonsense conception of group agents as “collections of human beings [which act] as if they were unitary agents, capable of performing like individuals” (List & Pettit, 2013, p. 1). The recent discussion of corporate moral agency has followed suit, asking how best to ascribe moral responsibility given that corporations are constituted by human members asserting their own individual agency, from which emerges a separate agent able to perform like an individual. Meanwhile, there is a noticeable lack of humanity in our initial discussions of AI and moral responsibility. Philosophers begin with an absence of humans in the system and work to explain (in many cases) where human responsibility best fits in.

This disparity may point to an important difference between AI and corporate moral responsibility. If this is true, we should consider our corporate moral responsibility practices in light of their human constituency. The solutions become primarily social, focused on circling the square of this odd quasi-human agent. It’s as if the corporation were an alien or a zombie — it is not like us in important ways, but enough like us that we may want to apply moral obligations and rights to it or to us concerning it.

AIs, on the other hand, are first and foremost technical systems. In addition to social considerations, we are able to consider AI’s technical makeup and apply technical innovation to help overcome our responsibility problems. The philosophical discussion focuses on the actions of the AI removed from humans and driven by the black box of its decision making infrastructure. Examples concerning self-driving cars, autonomous weapons systems and facial recognition software remove humans from the system’s actions except as targets for injury or injustice.

Commonsense bears this out. Corporations are made of people (an employee may consider themself part of a corporation) while AI are made of computer code (they exist on servers or in a computer). If these systems are truly as different as this, it would be a mistake to try to group them under the category of AAS and focus analysis on that. We would lose out on important tactics for solving these problems: technically in the case of AI and societally in the case of corporations.

However, these idealized views of the corporation and AI do not accurately reflect reality. AIs are sociotechnical systems, as dependent on societal infrastructure as they are on technical infrastructure. The modern corporation 5 is also a sociotechnical system, and in both systems we see agency instantiated in the technical side of the system. This agency actively sheds dependencies on direct human involvement.

5.1 AIs are Sociotechnical Systems

I’ll take the sociotechnical nature of AI first, as it has been emphasized previously (see Vallor & Vierkant, 2024). While it seems most of the action of an AI — its ingestion and interpretation of inputs to produce novel outputs — occurs in a self-contained, dynamic system, in fact AIs rely on a large array of human social practices to maintain and enable their continued existence and indeed to produce their actions. This is implied in various degrees by arguments for responsibility distribution we’ve seen above, but along with suggesting a potential (though problematic) out for the moral responsibility gap, the reliance on a social element also affects how we approach AI holistically.

We have already established that AIs are artificial (they are human-originated). The role of designers, users, companies, energy and regulatory infrastructure, and other social practices are crucial to start an AI’s program running, direct it to necessary inputs and keep it going. The social elements represent necessary components to an AI’s continuing function. Without recognizing this, the autonomy of AI systems is easy to overestimate.

I don’t mean to overemphasize the human element, though. AI is novel and philosophically relevant in part because the technology alienates human control from its outputs more so than other technologies. Considering this, we end up in a place where social practices are part of the AI system, but not necessarily. Humans are part of the AI system, but not in a way that establishes control in a morally meaningful fashion. Vallor and Vierkant argue that the moral performance of an AI as tool is can only be understood from the level of a sociotechnical system. I disagree, and show below that AI as technology (apart from its full sociotechnical system) has agency which separates its actions from that of the sociotechnical influences.

5.2 Corporations are Not Group Agents

Meanwhile, the description of corporations as group agents is no longer accurate. Categorizing corporations as a group agent places humans as a necessary constituent part of the entity. However, many corporations as they exist today — and certainly the largest corporations which produce the most outsized moral consequences on our communities — have been designed in much the same way as AI: to deemphasize human decision making.

Consider the membership makeup of the modern corporation 6. The agency of individual directors and shareholders is subordinate to the goals and representations (that is, the agency) of other AAS. When a decision needs to be made, the human members of a corporation are not lending individual judgment. Instead they are reflecting the incentives and dispositions of the AAS they represent, whether that be an investment group, a pension fund, another corporation or the corporation itself. The human members of the modern corporation repudiate personal agency and become components of the system. Activist investors can be an example of members defying this disavowal of agency, but these aberrant actions help illustrate that corporations are not expecting or designed to be run as an aggregation of human intention — as a group agent.

Hyper-complex corporations rely little on human agency to make corporate-wide decisions, particularly those that are the most morally loaded. Corporate actions, then, should not be described as aggregation of human intention but are better described as the outcome of interactions between the entity and systems like stock exchanges, governments and other corporations.

While this holds distinctly for mega corporations, we also see distancing from human agency in the creation of shell companies and special-purpose entities. Decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) represent a relatively new corporate structure (not legally recognized everywhere) in which governance and management of a corporation is automated and executed through a program on a blockchain with up to no human intervention (Rikken et al., 2023). Consider that corporations can create subsidiary corporations, and it becomes not just possible, but likely to have corporations with human origination, but without humans associated with the corporation itself.

The purpose of incorporating, you might say, is to deflect all of our responsibility practices away from human actors (as it explicitly is in the case of legal responsibility). Its nature is anti-humanistic. Humans can be said to be part of the makeup of the typical modern corporation, but are not a necessary part. Social practices affect the corporate sociotechnical system, but not in a way that establishes control in a morally meaningful fashion. The technology of the corporation, that is, the structures and processes that produce decisions, has agency which separates its actions from that of its sociotechnical influences.

A corporation, then, is not a group agent and it is a mistake to categorize corporations as such. Corporations, like AIs, are sociotechnical systems with technical cores that have variable levels of reliance on human action. We cannot differentiate these systems from each other or from other systems by the nature of human participation with the system. We should instead look to agency.

I write about this in more depth in the next section.

6. Avoiding the Problem of Many Hands

It may be the case that AI, corporations and analogous complex systems raise similar enough ethical issues that it would be preferable to treat them as a category. If so, we could also look more broadly. Are the problems described with AAS best addressed at an even wider scope?

Perhaps the ethical obstacles of AAS are examples of the many hands problem, which we see not only in artificial agential systems but in other complex interactions like the phenomena which bring about global climate change (van de Poel et al., 2012). The problem of many hands (PMH) is a situation in which, “due to the complexity of the situation and the number of actors involved, it is impossible or at least very difficult to hold someone reasonably responsible” (van de Poel et al., 2012, p. 50) 7.

Take AI for instance. When we establish that there are responsibility gaps regarding the actions of AI, it is often due to the sociotechnical systems that create and maintain them. Were a single inventor to program a powerful AI which then went mad, we could ascribe a healthy amount of responsibility to the individual inventor, similar to how we may blame adults for the transgressions of their misbehaved pets. The so-called responsibility gap for AI, then, only occurs when the forces creating, maintaining and sustaining the AI are more diffuse. In fact, this is likely to happen when a corporation or multiple corporations are operationally responsible for the AI.

What we come to in this case is that the AI responsibility gap problem reduces to problems of corporate moral responsibility. The problems we recognize in ascribing responsibility for the outcomes of AI systems exist because they are the same problems we have ascribing responsibility for corporate actions.

Morally loaded corporate actions, for their part, are examples of PMH. Modern businesses are built to exploit efficiencies and advantages of specialization and division of labor. Therefore, for any project or initiative the company undertakes there are many people doing discrete parts of the work to create an overall outcome. Add in support and operational functions and you have an extremely complex group of interactions. Backward-propagating responsibility for outcomes would be very difficult (though not impossible as Floridi shows above) and would not result in holding anyone responsible to a sufficient degree, hence the PMH.

So at this point we have a situation where our AI responsibility problems have been subsumed into the corporate case and our corporate case is well-described as the problem of many hands. Rather than focusing on AAS, why not focus our efforts on PMH, which can additionally lead to insights into societal tragedies such as humanitarian crises, food safety outbreaks and climate change?

Unfortunately, while addressing our moral practices concerning PMH is laudable, PMH does not apply in the case of AAS. PMH occurs where individual responsibility and the impact of individual agency is minimal. AAS’, on the other hand, actively suppress and disintegrate individual agency, replacing it with the agency of the technical systems.

PMH exists in situations with many actors or in collective settings. A collective here, and the actors described, are people or groups of people acting with individual agency. As I discussed earlier, however, the acts of corporations do not reduce to the acts or intentions of individuals. The actions of corporations are better described as the outcomes of interactions between the entity and other systems. The technology of the corporation suppresses the individual agency of the people involved in corporate decision making by design and replaces it with the representations and goals — that is, the basic agency — of the corporation or other AAS. This agency disintegration creates people who act as components of a system. Vehicles of agency rather than acting as agents themselves. And that is where people are the actors in a process. Often the activity of suppliers, competitors and markets, which instantiate as representations within the AAS, dictate actions well before human consideration.

AI as technology has a separate agency from the sociotechnical system that creates and sustains it. The capacities for AI to learn, and thereby create unpredictable outcomes, separate it from the goals and representations of its originators. This is the reason for the responsibility gap and why it cannot be subsumed into the corporate case. Like corporations, AI actions are decided based on representations and goals within the technological system itself. The intentions of sociotechnical actors such as users, corporations which build AI, designers and other groups are influential but secondary to the agency of the AI.

In the case of humans, I argued that people can have their agency effectively disintegrated in their roles as corporate members. This does not mean they’ve lost all their agency, just their agency in their role within the corporate system. Similarly, a sufficiently strong AI that is used by a corporation could have its agency disintegrated in its role in a corporate system (say as a part of a DAO). Like a person, the AI as technology would still have agency separate from the corporate agency. In fact, one of the current practical problems of AI systems is that they display more agency than human employees, in notable cases coming to unpredictable outcomes that are damaging to the corporations employing them.

Let’s turn to the case of the single inventor who creates an AI which then goes mad. The responsibility attribution in this case is less straightforward than it looks. Consider a single entrepreneur who founds a multinational corporation which at some point in the future has morally negative effects. The responsibility ascription to the founder would not be based on her creation of the company, but on her continued involvement in the running of the company. An autocratic leader of a single-member company might hold significant responsibility, while a company founder who is not an active member of the current running of the company (in the time period relevant to the negative actions) would not. Like a corporation, AI as technology changes over time as new inputs and representations are addressed to the system. An inventor who exercises heavy control over the working of an AI throughout its operation would be able to hold much of the responsibility for its outputs (one might also ask if this is actually AI 8), whereas an inventor whose AI goes rogue after years of operation in a complex informational environment may not. In short, the creation of the system is different from the running of the system.

Add to this that AI technologies, like corporations, have powerful agency disintegration effects. As Vallor and Vierkant put it, AI technologies “often disperse the contributions of human will, introduce more chaotic and random effects in action chains, and sever the cognitive and motivational links between means and ends that give actions moral meaning” (2024, p. 17). As with the corporate technology, AI as technology suppresses human agency as inputs are transformed into outputs.

Artificial agential systems, then, have qualities that prevent them from being considered as cases of PMH. As agential systems, they interrupt human agency in favor of their own. In modern corporations this takes the form of dependencies, contracts, processes and relationships that prioritize system-level representations and goals. In AI this presents as black box functions that alienate human intention from system output.

Does this split from human agency also make the outcomes caused by AAS morally neutral? Perhaps these outcomes cannot be morally loaded positively or negatively and are similar to outcomes caused by hurricanes or luck. This could pose a problem for my argument, and comprehensively defending it is beyond the scope of this discussion, but I believe the act of human origination, that is, AAS’ artificial nature, enables outcomes caused by AAS to remain morally loaded. A future analysis could combine human origination and a holistic view of our moral ecosystem to maintain moral valence throughout the process, separate from agency.

7. Implications of AAS

If, as I argue, artificial agential systems are an appropriate categorization of the systems we create that present at least basic elements of agency, the moral positioning of AI and corporations can be combined into a coherent whole.

This view draws most from arguments of Sepinwall, Vallor and Vierkant, and others who would have us reconsider our primarily backwards-looking method of ascribing responsibility in the case of corporations and AI. I break from them, Vallor and Vierkant in particular, by stressing the agency of the technical systems separate from an agency derived from the sociotechnical systems of which these entities are a part. Due to its constitution, the technical aspect of an AI or corporate sociotechnical system actively works to disintegrate the agency of surrounding entities, including associated individuals and the sociotechnical system of which it is a part.

Acknowledging AAS with these features both bolsters and rebuts arguments in the general debate we’ve seen so far.

Firstly, my argument reinforces List and Pettit’s irreducibility conclusion. Corporate-level decisions are irreducible to the beliefs and preferences of the membership as individual agents. This isn’t due to examples such as the discursive dilemma, however. It is because corporate members do not exercise their agency in the modern corporation. They represent the intentions of other AAS, or the corporation as AAS.

Because of this, my argument stymies efforts for distributive responsibility in both AI and corporate cases. As we’ve seen, the nature of AAS is such that at sufficient complexity they break the intentional link between people and system. Design and user intent do not have the regulative effects they should to create responsibility, and in cases where AAS require human activity to function they can do so without human agency.

Finally, my argument supports Sepinwall, Vallor and Vierkant’s emphasis on mutual recognition as necessary for moral interaction. AAS are likely to adapt and proliferate in the coming decades. While it is only possible that we could develop AAS that has the capacities for vulnerability and mutual recognition so as to be considered moral agents or patients, it is guaranteed that AAS as it exists today — as agency disintegrating — will continue.

Emphasizing mutual recognition in our morality practices creates a powerful incentive to combat agency disintegration individually and communally. A moral rejection of agency disintegration would change our relationship with AAS. While it wouldn’t eliminate AAS’ hostility toward human agency, it would allow us to better identify and mitigate the dangers these systems pose to our moral landscape. In fact, as corporations maintain a dominant societal position and as AI’s impact grows, such mitigation strategies have become essential to the continuing function of our moral environment.

AAS are a part of our moral ecology, but not as agents which can be held morally responsible or be equal participants in our moral practices. Instead their makeup and actions must be integrated as part of a responsibility all people have to develop as moral agents. A responsibility to create, cultivate and negotiate a morally thriving world. AAS are powerful mechanisms to obfuscate and destroy human agency. They can also lead to profound innovation, prosperity and knowledge. By exercising our moral judgment, reasoning and regulation we can balance the moral risks of AAS for the good of all.

8. Conclusion

The level of human agency required for the functioning of technologies and businesses is variable. Each can act with close interaction between human and system. In these cases our moral intuitions and practices can generally be exercised as-is. But when the technology becomes agential a split appears which places it in a different ethical position. This gap is created by system agency that separates itself from human agency. AIs and corporations are both technologies that proactively widen this gap.

Artificial agential systems (AAS) create unique and troubling moral problems relating to responsibility, accountability and agency cultivation. I have argued that corporations and AI, as AAS, have significant overlap in their moral positioning. Considering AAS as a whole allows us to better recognize the agency disintegrating power of these systems, and reveals tangible opportunities for improving our moral environment.

To get here, I gave a brief overview of the debate surrounding corporate moral responsibility and AI and responsibility. From there I drew parallels in the debates and grouped them under the category of artificial agential systems. Those parallels include effects on agency and the componentized makeup of the systems. I then showed how this can explain the similarities in the discursive turns in both debates.

I considered two objections: that the categorization goes too far and that it does not go far enough. As a counterargument to the idea that AI and corporate responsibility positions are distinct, I showed that the lack of human input in the case of AI is overblown, and the focus on human input in the corporate case misrepresents reality. In fact, both systems are sociotechnical systems in which the technical side of the system actively minimizes human agency. To rebut the idea that the problem can be reduced to the problem of many hands I further illustrated this tendency to minimization and human agency disintegration.

Ultimately, I show that artificial agential systems are an important conceptual categorization of two sources of pertinent problems in our moral landscape. By acknowledging the nature of AAS and addressing the lack of mutual recognition accentuated in current AAS we can begin to rectify existing moral problems and develop a healthier moral environment.

References

Björnsson, G., & Hess, K. (2017). Corporate Crocodile Tears?: On the Reactive Attitudes of Corporate Agents. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 94(2), 273–298

Bohn, D. (2016, October 19). Elon Musk: negative media coverage of autonomous vehicles could be ‘killing people’. The Verge.

Business Roundtable. (2016). Principles of Corporate Governance. BusinessRoundtable.org.

Coeckelbergh, M. (2020). Artificial Intelligence, Responsibility Attribution, and a Relational Justification of Explainability. Science and Engineering Ethics, 26(4), 2051–2068.

Davis, M. (2012). “Ain’t No One Here But Us Social Forces”: Constructing the Professional Responsibility of Engineers. Science and Engineering Ethics, 18(1), 13–34.

Floridi, L. (2016). Faultless responsibility: on the nature and allocation of moral responsibility for distributed moral actions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 374(2083), 20160112.

French, P. A. (1984). Collective and Corporate Responsibility. Columbia University Press.

Goetze, T. S. (2022). Mind the Gap: Autonomous Systems, the Responsibility Gap, and Moral Entanglement. 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 390–400.

Hasnas, J. (2017). The phantom menace of the responsibility deficit. In E. W. Orts & N. C. Smith (Eds.), The Moral Responsibility of Firms. OUP Oxford.

Himmelreich, J. (2019). Responsibility for Killer Robots. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 22(3), 731–747.

Hindriks, F., & Veluwenkamp, H. (2023). The risks of autonomous machines: from responsibility gaps to control gaps. Synthese, 201(1).

Katersky, A., Deliso, M., & Pezenik, S. (2025, February 21). Luigi Mangione’s defense cites evidence concerns, no trial date set. ABC News.

List, C. (2021). Group Agency and Artificial Intelligence. Philosophy & Technology, 34(4), 1213–1242.

List, C., & Pettit, P. (2013). Group Agency: The Possibility, Design, and Status of Corporate Agents (Illustrated). Oxford University Press.

Matthias, A. (2004). The responsibility gap: Ascribing responsibility for the actions of learning automata. Ethics and Information Technology, 6(3), 175–183.

Meko, H. (2025, February 21). Suspect in Insurance C.E.O. Killing Creates Website as Support Floods In. The New York Times.

Moen, L. J. (2023). Against corporate responsibility. Journal of Social Philosophy, 55(1).

Nihlén Fahlquist, J., Doorn, N., & Van de Poel, I. (2015). Design for the Value of Responsibility. In J. van den Hoven, I. van de Poel, & P. Vermaas (Eds.), Handbook of Ethics, Values, and Technological Design: Sources, Theory, Values and Application Domains (2015th ed.). Springer.

Nyholm, S. (2018). Attributing Agency to Automated Systems: Reflections on Human–Robot Collaborations and Responsibility-Loci. Science and Engineering Ethics, 24(4), 1201–1219.

Pettit, P. (2017). The Conversable, Responsible Corporation. In E. W. Orts & N. C. Smith (Eds.), The Moral Responsibility of Firms (1st ed.). OUP Oxford.

Reyes, C. L. (2021). Autonomous corporate personhood. Wash. L. Rev., 96, 1453.

Rikken, O., Janssen, M., & Kwee, Z. (2023). The ins and outs of decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) unraveling the definitions, characteristics, and emerging developments of DAOs. Blockchain: Research and Applications, 4(3), 100143.

Rönnegard, D., & Velasquez, M. (2017). On (Not) Attributing Moral Responsibility to Organizations. In E. W. Orts & N. C. Smith (Eds.), The Moral Responsibility of Firms (1st ed.). OUP Oxford.

Sepinwall, A. (2017). Blame, Emotion, and the Corporation. In E. W. Orts & N. C. Smith (Eds.), The Moral Responsibility of Firms. OUP Oxford.

Sepinwall, A. (2024). Artificial Moral Agents: Corporations and AI. In S. Hormio & B. Wringe (Eds.), Collective Responsibility: Perspectives on Political Philosophy from Social Ontology (pp. 27–48). Springer Nature.

Stahl, B. C. (2006). Responsible computers? A case for ascribing quasi-responsibility to computers independent of personhood or agency. Ethics and Information Technology, 8(4), 205–213.

Strawson, P. F. (2008). Freedom and Resentment. In Freedom and Resentment and Other Essays (1st ed.). Routledge.

Taylor, I. (2024). Collective Responsibility and Artificial Intelligence. Philosophy & Technology,37(1).

Tigard, D. W. (2020). There Is No Techno-Responsibility Gap. Philosophy & Technology, 34(3), 589–607.

Vallor, S. (2023, July 14). Edinburgh Declaration on Responsibility for Responsible AI. Medium.

Vallor, S., & Vierkant, T. (2024). Find the Gap: AI, Responsible Agency and Vulnerability. Minds and Machines, 34(3).

van de Poel, I., Nihlén Fahlquist, J., Doorn, N., Zwart, S., & Royakkers, L. (2012). The Problem of Many Hands: Climate Change as an Example. Science and Engineering Ethics, 18(1), 49–67.

Vargas, M. (2013). Building better beings: A theory of moral responsibility. OUP Oxford.

Vargas, M. (2021). Constitutive instrumentalism and the fragility of responsibility. The Monist, 104(4), 427–442.

Footnotes

As of writing a trial date has not been set in the Mangione case (Katersky, et al, 2025)↩

I am using types of responsibility outlined by Vallor (2023) in the case of AI, but similar relevant discussion can be found in Davis (2010) (responsibility-as-simple-causation and responsibility-as-liability taking the place of causal responsibility and legal responsibility, respectively).↩

Moving forward I refer to these as Pettit’s criteria though he, Christian List and Peter French (1984) have written similarly on the subject.↩

This cascading does not have to be redistributive, as I’ve already discussed some of the issues there.↩

I use the term ‘modern corporation’ to separate the romanticized concept of a corporation from the complex, hyper-connected and legalized institutions present today.↩

In many discussions of corporate agency, employees, contractors, and other people hired by a corporation are considered part of the 'membership' of a company (see Björnsson & Hess, 2017). I support a more constrained definition of membership drawn on the shareholder model of corporate governance dominant today. In this model a company's board of directors and executive management are decision making authorities. Employees, suppliers and communities are stakeholders, but not active members of the decision making process (except in overlapping roles as shareholders or board members).↩

In the cited work, van de Poel, et al. later redefine PMH: “A problem of many hands occurs if there is a gap in a responsibility distribution in a collective setting that is morally problematic.” This better addresses both backward- and forward-looking responsibility practices but deemphasizes complexity of the interactions as a requirement, only specifying that it be in a collective setting and morally problematic. I am using the former definition to highlight the complexity of interactions and the act of being held responsible rather than being morally problematic.↩

A similar case can happen with corporations: an autocratic, single-member corporation is prevented from becoming agential.↩